Schutzhund--Devotion to Quality Breeding and Progressive Training

by Lori Rodriguez | Published March 1995 in DogWorld Magazine - The World's Largest All Breed Magazine. Reprinted by permission in The German Shepherd Quarterly

What is Schutzhund?

In 1903, recognizing the detrimental effects of breeding for fashion and what Max vom Stephanitz (the father of the German Shepherd Dog) called "kennel breeding" (the keeping and breeding of many dogs), the Verein für Deutsche Schäferhund (SV) drew up a scheme of tests to evaluate the breeding programs of their emerging, yet beloved German Shepherd Dog.

These tests or "efficiency trials" were known as "Der Deutsche Schäferhund als Diensthund" (the German Shepherd Dog as Service Dog and were also used to prove the breed's value to the police and military. Over time "Diensthund" (Police Dog) evolved into the broader "Schutzhund" (Protection Dog)--the sport enjoyed worldwide today.

The Schutzhund Trial

The Schutzhund Trial is a series of complex tests designed to make breeding from ignorance or callousness less rewarding, if not downright difficult. Each dog must prove he is of sound mind and body or is deemed unworthy for breeding. The ignorant or callous breeder cannot produce dogs (in any consistent manner) of the caliber necessary to pass muster and are therefor discouraged from breeding altogether. In addition, the considerable time and effort spent training and conditioning the dog develops a greater understanding of the physical and mental attributes required of the breed, further promoting good breeding practices. And, consequently, the quantity of one on one time necessary for training encourages deep bonds, mutual respect, and a good relationship between trainer and dog.

The Sport in the United States

The sport of Schutzhund gained a firm foothold in this country in 1978 when The United Schutzhund Clubs of America (USA) filed Articles of Incorporation. The Deutscher Verband der Gebrauchshundsportverein (DVG), translated: German Club for the Sport Dog, was founded in 1980 and continues in full force today. In the early '80s, the now defunct North American Schutzhund Association (NASA), was also formed to campaign for the sport on this continent, but quickly lost ground as USA and DVG underwent rapid growth. Despite an overall antidog atmosphere in many communities, the sport of Schutzhund continues growing in popularity--to the great benefit of the breeds involved.

In 1991 the American Working Dog Federation (AWDF) was founded to "preserve the working breeds and develop lines of communication between breed clubs." Recognizing the value of the ideals held by the AWDF, the following breed organizations have joined the federation: the United Schutzhund Clubs of America (a German Shepherd breed club), contact Gordon Esselmann 407-323-5023; the United Doberman Club, contact William Knox 615-526-4643; the Working Schnauzer Federation, contact Ed Weiss 314-567-7521; the Working Boxer Association of America, contact Mark Chase 508-748-3976; the United States Rottweiler Club, contact Jacqueline Rousseau 602-979-3765; the North American Working Bouvier Association, contact David Evans 517-339-0570; United Belgian Shepherd Dog Association, contact Jean-Claude Balu 714-823-4386; and the Federation for the American Staffordshire Terrier, John Thomspon 407-323-5023. Combined membership for these organizations totals over 12,000. With the inception of the AWDF, Schutzhund and its related sports should see healthy growth for generations to come. This growth will have a tremendously positive impact on the quality of dogs produced in this country.

A Truly International Sport

Schutzhund trials worldwide generally follow one set of rules set forth by the Verein für Deutsche Hunde (VDH), the German regulatory organization for rules and regulations. Slight adjustments to the rules are made by the VDH from time to time as the sport continues to evolve. Each year world championships are held - one all breed championship (the FCI World Championship) and several breed specific world championships. The German Shepherd Championship is called the WUSV World Championship and is held in a different country each fall. The WUSV World Championship will be held in Boston, Massachusetts in 1998; this will be the first time the United States will hold this major event. Last year the following countries sent teams to the WUSV World Championship: Argentina, Belgium, Canada, China (Taiwan), Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Austria, Slovenia, Czechoslovakia, Spain, Poland, United States of America, and Switzerland --23 countries in all.

The Basics

A Schutzhund Trial, is broken down into three distinct phases each worth 100 points (300 points for a perfect score). The first phase is tracking, which tests the dog's scenting ability, trainability, and physical and mental endurance; the second is obedience, which tests the dog's overall temperament, structural efficiencies, and willingness to work for his handler; the final phase is protection, which tests the dog's courage, physical strength, stability, and obedience and character while in a higher drive.

There are three levels of achievement called titles or degrees. The dog must pass his Schutzhund I (the first level) before he is allowed to compete at the next level and he must pass the Schutzhund II before being able to compete for his Schutzhund III (the final level). At the start of the trial, the judge performs a brief temperament evaluation on all participating dogs. Overly aggressive or uncontrollable dogs are dismissed from the trial before ever stepping onto the competition field! The dog must then achieve a minimum score of 70 points in tracking, 70, points in obedience, and 80 points in protection under an authorized judge during an authorized event in order to pass and proceed to the next level. All three phases are done in succession on the same day and all three must be passed on that day. Because of the length of time necessary to evaluate each dog, the trial is limited to just 12 dogs per day. At a typical trial, competitors (and hardy spectators) meet for tracking at 6:30 a.m. and often work through till late in the afternoon, making for a grueling, but exciting day!

At least two weeks prior to competing for his Schutzhund I title, a dog must pass the "Begleithunde" or "Companion Dog" test at an approved Schutzhund Trial. The "B" was developed as a preliminary character evaluation test involving a shortened obedience (Pass/Fail) routine (see "Obedience" below) plus a traffic safety examination involving joggers, crowds, bikes, cars, loud noises, gun shots, bells, and strange dogs - all designed to weed out overly aggressive or nervous dogs from the gene pool and discourage those dogs from participating in the sport. All dogs must pass the "B" to prove they have sound temperament before being allowed to compete for a Schutzhund title.

All scores (even failing ones) are recorded in a dog's scorebook which is presented to the judge at the start of each trial. If a dog does not complete all phases of the trial, the reason(s) for his dismissal are also recorded. A copy of the trial results are filed with the main office.

Tracking

The tracking portion of the Schutzhund III title consists of a track of approximately 800 normal paces at least sixty minutes old, laid by a stranger with three articles and four 90° turns. The handler follows the dog on or off leash 10 meters (approximately 33 feet) behind.

The only visible indication of the track is the starting flag. The scent of the track must not be disturbed when an article is placed (the track layer must not scoff or stop). The articles, which must not differ in color from the terrain, cannot be greater than the size of a wallet and are often much smaller. One dog/handler team reports to the judge and then begins the track. At the start of the track, the dog must take sufficient time to absorb the scent, he must pick up the scent and proceed with a deep nose. Air scenting or varying from the exact track is penalized. A slow, methodical tracking dog is preferred--accuracy, not speed is prized. The dog is judged on his intensity, confidence, accuracy, and obedience on the track.

When the dog finds an article, he must immediately indicate that he has done so without being influenced by the handler. The indication can be accomplished by lying down, sitting, or a standing stay. (The dog may also indicate the article by picking it up.) The handler drops the leash and proceeds to the dog. He lifts the article high in the air to indicate to the judge that the article has been found. The handler then gives the command to continue the track, again following 10 meters behind the dog. When the dog finds the third article, the track is completed. The team reports back to the judge, presents the articles to him, and stands for critique. A detailed critique is given and addressed to the audience. To compete successfully on a national level, a dog should be able to track 97-100 points consistently!

Obedience

After all the dogs finish tracking, the obedience takes place. The ideal field is about the size of a regulation soccer field. Two dog/handler teams report on field to the judge. One handler is instructed to place his dog in a long down and move 40 paces away and out of sight. This dog must remain in the down position without influence from the handler while the other dog completes all but the last exercise. He must remain motionless in the designated spot until picked up by the handler.

The second team begins their exercises once the first handler is out of sight. All exercises start from the basic position (dog sitting on the left of the handler his shoulder even with the handler's left leg) and are performed off leash. The handler is only permitted to use a voice command when starting the exercise or when changing pace. Hand signals are not allowed and body language is pointed as handler help. When the handler comes to a stop, the dog should come to the sit position without command. The team must be precise and spirited. The dog should perform the exercises quickly, willingly, and without extraneous handler help. Dogs that are slow to perform the exercises or show stress are pointed heavily.

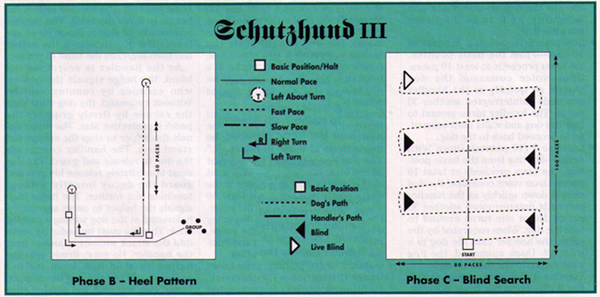

Figure 1

The first exercise is heeling off leash (10 points): The heel pattern is described in Figure 1. During the heel pattern, as the dog and handler are moving away at least two gun shots (6-9mm) are fired; the dog must remain indifferent to the gun noise. Should the dog demonstrate gun insecurity, he is to be dismissed from the trial.

Exercise 2 (5 points): Sit Out of Motion. From the basic position, the team proceeds at least 10 paces, upon voice command the dog should sit quickly as the handler proceeds uninterrupted another 30 paces. He turns around to face the dog and wait until instructed to proceed back to the dog.

Exercise 3 (10 points): Down With Recall. Starting from the basic position, the team proceeds at least 10 paces, upon voice command the dog should down quickly as the handler proceeds uninterrupted another 30 paces. He turns around to face the dog. When requested by the judge he calls the dog to a front sit. Upon command, the dog must return to the basic position.

Exercise 4 (5 Points): Stand Out of the Walk. From the basic position, the team proceeds at least 10 paces, upon voice command, the dog should come quickly to the stand position as the handler proceeds uninterrupted another 30 paces. He turns to face the dog. When requested by the judge, he returns to the dog and commands the dog to sit.

Exercise 5 (10 points): Stand Out of the Run. From the basic position, the team proceeds at a run for at least 10 paces, upon voice command, the dog should come quickly to the stand position as the handler proceeds at an uninterrupted run another 30 paces. He turns to face the dog. When requested by the judge, he calls the dog to a front sit. Upon command, the dog must return to the basic position.

Exercise 6 (10 points): Retrieving a Dumbbell Weighing Two Kilograms (approximately 4.25 lbs) on the Flat. From the basic position and upon command, the dog should retrieve a dumbbell which has been tossed approximately 10 paces away. The dog returns with the dumbbell to a front sit. The handler commands the dog to release it, then to return to the basic position.

Exercise 7 (15 points): Retrieving a Dumbbell Weighing 650 Grams (approximately 2.5 lbs Over a Meter High Brush Hurdle. From the basic position and upon command, the dog should jump over the hurdle, retrieve the dumbbell, return over the jump with the dumbbell and come to a front sit. The handler commands the dog to release the dumbbell, then to return to the basic position.

Exercise 8 (15 points): Retrieving a Dumbbell Over the Inclined Wall (1.80 Meters High, @six feet, and 1.50 Meter Wide at the Bottom. From the basic position and upon command, the dog should scale the incline wall, retrieve the dumbbell, return over the wall, and come to a front sit. The handler commands the dog to release the dumbbell, then to return to the basic position.

Exercise 9 (10 points): Go Ahead and Down. From the basic position, the team proceeds at least 10 paces. The dog is then commanded to "go out." The handler remains in the spot where he gave the command as the dog moves at a fast pace in the designated direction for at least 40 paces. When requested by the judge, the handler commands the dog to lay down. At the request of the judge, the handler goes to the dog and commands him to the basic position.

Exercise 10 (10 points): Long Down Under Distraction. This exercised, mentioned earlier, is completed when the handler is requested by the judge to return to his dog and commands him to the basic position.

At the completion of both obedience exercises, the teams report to the judge and stand for critique. The critique is detailed in nature and addressed to the audience. The score is given at the end of each critique.

Protection

The final phase is the Manwork portion of the event. This phase is held after the obedience on the same field. The obedience equipment is removed and replaced with six hiding places (blinds) for the helper (decoy). See Figure 2 for layout. You will note that during this final phase, the dog is under complete control of the handler and is not allowed to touch the helper in any way except under attack or to prevent an escape. Even then, when commanded, the dog must release the grip immediately and guard the helper without touching him further.

The helper is placed in a blind out of sight of the dog. One team reports to the judge then proceeds down field to Blind 1. Upon command the dog searches the blind, the handler commands the dog to come and redirects him to Blind 2. This continues until the dog finds the helper. (5 points)

Upon discovery, the dog must not touch the helper in any way but indicates to the handler by barking that he has found the decoy. Upon the judge's request, the handler walks to within four paces of the dog. The dog must remain intently barking at the helper. The handler then calls the dog to the basic position. The handler orders the helper to leave the blind. The handler commands the dog to down. He leaves the dog to search the helper and then searches the blind. (5 points)

As the handler is searching the blind, the judge signals the helper who escapes by running swiftly. Without command, the dog must stop the escape by firmly gripping the padded protective arm. The judge signals the helper to stop the escape and stand firm. The handler commands the dog to release and guard. The dog must immediately release his grip and guard the decoy intently without touching him further. The judge then signals the helper to move aggressively forward into the dog waving a padded stick. The dog must immediately move into the attack without influence from the handler. He must firmly grip the helper to stop him from further aggression. When the dog has gripped firmly, two hits with the padded stick are executed. (The hits from the padded stick are carefully placed and are not painful but create a threatening sound.) Upon direction from the judge, the helper again stands still and the handler commands the dog to release the grip. The handler goes to the dog and commands him to the basic position. (35 points)

The handler directs the helper to move forward as the dog and handler heel 5 paces behind for a distance of 50 paces and two turns. (5 points)

After 50 paces, the helper will turn without warning and attack the handler. The dog must stop the attack without command. When directed by the judge, the helper stops the attack and stands still. The handler commands the dog to release and guard. The helper is then disarmed. The dog, handler, and helper then proceed to the judge who is 20 meters away. The dog is heeling between the handler and the helper and may not bother the helper during this side transport back to the judge.

After reporting to the judge, the team heels down field as the helper leaves and a second decoy moves into a blind midway down field. When the team is ready, the judge signals the helper out of hiding. The handler calls to the helper to stop, but he turns and runs away from the team. The handler calls again, but the helper ignores him. The handler then gives the command to pursue and releases the dog. When the dog is 40 paces away from the helper, the judge signals the helper to turn and charge at the dog threatening him with the padded stick. The dog must not show signs of intimidation, but continue the pursuit confidently into the grip. After catching the dog, the helper will briefly continue forward into the dog then stop the aggression. The handler who is at least 40 paces away, commands the dog to release and guard. Upon direction of the judge, the helper reattacks the dog threatening with the padded stick. After the dog has gripped the protective arm firmly, the helper gives two stick hits and stops the aggression upon the judge's direction. The handler, who has not moved from his position 40 paces away, commands the dog to release and guard. When directed by the judge, the handler goes to the dog who has been intently guarding the decoy, and commands him to down. He then disarms the helper and takes the dog to the heel position, placing the dog between himself and the helper. The three proceed to the judge who is at least 20 meters away. The Attack, Pursuit, and Courage Test (10+10+25 = 45 Points)

After reporting to the judge. The team and the helper stand for critique. The critique is detailed and addressed to the audience.

The judge is required to dismiss any dog who does not release the grip or who leaves the helper. He may also dismiss a dog at his discretion should he feel the dog is not under sufficient control.

The Confusion Over Protection

Schutzhund without its protection phase is worthless as a breed evaluation tool. The protection phase is the most maligned, but crucial phase of the Schutzhund Trial. Because it is here where the dog's heart is tested, his true character challenged. The dog who is overly aggressive or uncontrollable will never be able to pass muster. So too the fear-biter, who lacks the courage to make the grade, is dismissed. These unwanted, dangerous characteristics are then systematically taken out of the gene pool. The nature of the dog is proven in the protection phase - to the benefit of the breed and society!

The Protection phase of this sport provokes some controversy because it involves biting sequences. However, anyone witnessing an authorized Schutzhund Trial can attest to the absolute control exhibited on and off the field. To many competitors, Schutzhund is a family sport. Children are often seen frolicking with their dogs before and after the dog leaves the protection field. This seems impossible or foolish to the uneducated. But this on/off switch is a product of good breeding and proper bite training - not junk yard, guard dog, attack training. Behaviorists call this stimulus control. Ricardo Carbajol states in his article "The Schutzhund Protection Test, Temperaments Quality Control" in the Jan/Feb 1994 issue of Schutzhund USA. "A side effect of stimulus control is that once you place the behavior on cue it is far less likely to occur unless the cue is given. In fact, so strong is this principle that animal behaviorists use it to get rid of unwanted behaviors such as digging, barking, licking, even biting. The principle simply is: if you don't want a behavior, put it on cue, and then don't give the cue.

In Schutzhund a variety of cues signal to the dog that it is time to do bite-work. The training field, the presence of blinds (portable hiding places for the decoy), a person dressed in a protection suit waving a stick in the air and making noises and threatening gestures are all clear go signals, much like a green light in an intersection. It is not hard to understand then, whey the same dog adopts neutral, normal and friendly behaviors when the cues disappear - when the sleeve and protection suit come off and the decoy, acting like a normal individual, invites the dog to be social. It is, by the same logic, not difficult to understand why the best trained Schutzhund dogs are by far the most predictable, trustworthy, and safe animals to be around on a daily basis."

The Universal Sport

Today, many breeds and thousands of people from Japan to Mexico enjoy training and competing in this fast-growing and fascinating dog sport. The sport transcends race, class, age, business and social affiliation, even many physical disabilities. Training, even for the serious competitor, is a social event in the sense that it is, by necessity, a club sport. Groups of people form nonprofit training clubs. The clubs are usually headed by a President who directs club activities and a Training Director who oversees and maintains the quality of the training.

At the Club the dogs learn social manners, obedience, and controlled protection. And the handlers learn to understand and motivate their dogs. The foundations and techniques for tracking are also discussed and debated at the training sessions. Clubs meet one to three times a week to train. Each dog and handler team also works out at home often putting in an additional one to two hours of training a day, five or six days a week. Obviously a well-conditioned dog with sound structure, stamina and a real love for work are prerequisites to training.

Reaping The Benefits

Besides the obvious benefits of such strict breed evaluation tests, there are numerous other reasons for the sports growing popularity and positive effect on the dog world. There is a tremendous challenge placed on the trainer (and the breeder) to help the dog become the most he can be both physically, through conditioning and good breeding practices, and mentally by developing his confidence, trust, enjoyment, willingness to work and intelligence to his fullest potential. This requires hard work and long hours spent studying behavior, training techniques, genetics, athletics, the breeds, and each dog individually. But when it all comes together, the results can be very rewarding. As a trainer, the communication, bond and teamwork experienced is absolutely thrilling! As an onlooker, a successful team is both awe-inspiring and beautiful to watch.

Not only must the dog enjoy his work, but he must be confident in his ability to handle stressful situations positively, and he must be taught to make correct decisions on his own. In meeting the challenges of training a dog for the sport of Schutzhund, the handler learns a lot about himself, his dogs, and the world around him. This is why the sport has such a tremendous hold on so many people.

And, because a joyful work attitude is required and a browbeat, downtrodden one is penalized severely, training methods that produce a happy, willing worker are encouraged, developed, and passed on, eventually making their way into the mainstream where the public can benefit.

A Good Dog is a Good Dog for the Sport

A good Schutzhund prospect is best described by the WUSV German Shepherd breed standard. (This is perfectly logical; remember, Schutzhund was developed as a breed suitable test!) "The German Shepherd that corresponds to the Standard offers the observer a picture of rugged strength, intelligence and agility, whose overall proportions are neither in excess or deficient in any way. The way he moves and behaves leaves no doubt that he is sound in mind and body and so possesses physical and mental traits that render possible an ever-ready working dog with great stamina.

With an effervescent temperament, the dog must also be cooperative, adapting to every situation, and take to work willingly and joyfully. He must show courage and hardness as the situation requires to defend his handler and his property. He must readily attack on his owner's command but otherwise be a fully attentive, obedient and pleasant household companion. He should be devoted to his familiar surroundings, above all to other animals and children, and composed in his contact with people. All in all, he gives a harmonious picture of natural nobility and self-confidence.

Sound nerves, alertness, self-confidence, trainability, watchfulness, loyalty and incorruptibility, as well as courage, fighting drive and hardness, are the outstanding characteristics of a purebred German Shepherd Dog. They make him suitable to be a superior working dog in general, and in particular to be a guard, companion, protection and herding dog."

An adult prospect can be judged by what one observes from the dog's scorebook and show card, his pedigree, and his character. The prospective puppy should be judged by his parents' scorebooks and show cards, pedigrees, and characters and then as an individual puppy. The puppy will more often than not prove his pedigree on the training field.

In Conclusion

Without adequate testing procedures, breeders have no way of proving the temperament of their breeding stock. Today, the effects of unchecked mental aptitude have resulted in temperament and physical problems in many breeds, including the German Shepherd Dog, - proof that fashionable and/or mass kennel breeding, so long ago forewarned against, create a heartache not only to their unsuspecting breeders, owners and society, but to the dogs themselves who must ultimately suffer with the physical and mental anguish of their breeders' folly. But hope is not lost. In fact, with the creation of the AWDF, as well as other performance-based dog clubs, and with the determination of farsighted breed clubs and individual breeders, there is much to be excited about!

Schutzhund is, therefore, more than a mere sport; it is a testament to the vision, devotion, and love man can have for his best friend!

Sources: The German Shepherd Dog in Word and Picture. by v Stephanitz. Copyright 1925 by the Verein fur deutsche Schaferhund. Reprinted 1982 by Hoflin Puplishing Ltd.

Schutzhund brochure and Schutzhund rulebook published by Shutzhund USA 1990's

The German Shepherd Book by Susan Barwig. Copyright 1986 Hoflin Publishing Ltd.

The German Shepherd Dog a Genetic History by Malcolm Willis, PhD. Copyright 1991 by Malcolm B. Willis.

WUSV German Shepherd breed standard

Personal interviews with schutzhund enthusiasts around the world